I’m an internationally exhibited textile artist.

No, really. Listen.

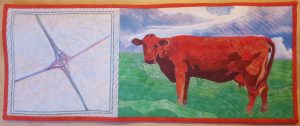

Here’s a little quilt that usually hangs in our hall. (I moved it into better light for the photograph.)

I made it in the summer of 2012 and submitted it for Ireland’s entry to the European Quilt Association exhibition. This exhibition is annual: each member country sends a certain number of quilts (ten, that year), and there’s a theme and a size requirement.

I rather like this quilt

It’s called “Red Cow Roundabout”. Let me tell you about it.

On the outskirts of Dublin, maybe half an hour from my house, squats the Red Cow interchange. It’s a huge junction, where Dublin’s ring road, the M50, crosses one of the country’s main arterial routes, the N7 (there’s a tram line in the mix too).

For the first couple of years after the M50 opened, the Red Cow Roundabout (as it was then) was a monumental bottleneck, its capacity totally inadequate for the volume of traffic inching through. So they redid it from scratch as a spaghetti junction, and now it works a lot better.

Although its official name doesn’t include the word “roundabout” any more, a lot of people still called it that for years, out of habit.

The theme of the EQA exhibition in 2012 was “Crossroads”, and as sometimes happens, the design for my quilt came rushing to mind almost as soon as I heard the theme announced.

There is no roundabout any more. Nor has there been any trace of a red cow in these parts for many a long year. So I put them together in a quilt that combines memory and record-keeping with the notion of journeying forward.

The left-hand section is a quilted map of the junction as it is now (or at least, was in 2012), and on the right you see the reddest-looking cow I could muster.

My quilt was one of the Irish entries in that year’s EQA exhibition. They were shown at the Festival of Quilts in Birmingham, and they then went on a kind of grand tour around Europe, stopping off at various other festivals, guild AGMs, and similar.

So, there you go.

This is a textile art piece, I made it, and it has been exhibited in several countries. Therefore, I’m an internationally exhibited textile artist. Quod erat, I think you’ll find, demonstrandum.

Of course, there’s the voice

The “not really, though” voice. The voice that says I can’t possibly describe myself in these terms until I’ve had, like, a solo exhibition in some venue that no human on the face of this planet has not heard of.

That voice? It has standards. It knows what phrases like “textile artist” and “internationally exhibited” really mean – and no offence, honey, but it’s not one measly little art quilt that just happens to have gone on tour.

Do you belittle your achievements like this?

I’ll be honest with you: I almost deleted this post, because I’m embarrassed about it. I’m afraid you may think I’m puffing up my tiny achievement into “something it’s not”.

(Oh, me. I mean, I love me, but could I please give me a break?)

It’s all about what “counts”, isn’t it?

When it comes to identifying as an artist, some things obviously “count” – the aforementioned solo exhibition, grants and awards, people buying your work (…especially if the price tag covers materials and labour at more than minimum wage…).

Equally, other things probably don’t really “count” – making something from a kit or someone’s step-by-step instructions, doodling curlicues on the back of an envelope during a meeting, darning a worn spot in the elbow of a cardigan.

But there’s a lot of in-between space here. Really, a lot. (To tell you the truth, I had a hard time coming up with things for the “don’t count” list, because I could totally imagine ways in which all of the activities I mentioned could be incorporated as part of an artist’s practice.)

And in that in-between space, there’s a lot of room for unhelpful assumptions.

Someone says they’re an author, and we think, “Oh, like J.K. Rowling.”

They say they’re a painter, and we think, “Oh, like Frida Kahlo.”

They say they’re an actor, and we think, “Oh, like Meryl Streep.”

Then, if we aspire to claim a similar label for ourselves, we adopt the strictest possible criteria for that label. Anything less, we tell ourselves, “doesn’t count”.

It’s a fear thing.

We’re afraid we’ll say, “I’m an artist,” and someone will say, “No you’re not.”

Boom. Crash. Doombiscuits all round.

So who gets to decide what counts?

When it comes to my artistic practice, am I allowed to decide for myself what counts?

Well, am I?

I say I am.

See, now it’s about permission. It’s about mindset. It’s about my entitlement to stand up and tell you about this thing I did, with the implication that it’s a real thing that counts.

Here’s another question

Having read this post, do you believe me when I assert that I am an internationally exhibited textile artist?

If you don’t believe me, why not? What do you believe I would have to do to earn the right to claim this label? Where is your line?

(And forgive me for asking, but how do you propose to enforce it?)

If you do believe me – and this is my real point here – what does that give you permission to say about yourself, and about your work?